Image above: vineyards in Wolxheim, Alsace, 2023, Jan Eckert.

The original German Version of this text was published in January 2024 on:

https://janeckert.ch/blog/hortopia-i/

Although I appreciate the element of a caesura, such as the turn of the year, in many forms of expression, I tend to think in terms of continuity, and so this blog post ties in with the past few months, which have been marked by various texts, travels and people. At the same time it is a dreamy outlook (more on this term later) on what may yet come, or what we want to see coming.

Destroying

«anéantir» – Michel Houellebecq uses this seemingly inconspicuous word (the effect is accentuated by the lower-case spelling of the title in the French edition published by Flammarion) as the title of his last novel. It probably only unfolds its full scope and power when translated into one’s own language. Translated into English, anéantir means «to destroy».

I came across the text in early 2023, and it was probably the reaction to the global political and ecological situation that prompted me to read the controversial author’s seven-hundred-page work. It was to be the starting point for several weeks of reading all Houllebecq’s texts available to me, always accompanied by the ups and downs, hope, deconstruction and resignation of his protagonists. While I will talk about hope in what follows, after a series of encounters over the past few months, I would like instead to vehemently call into question resignation.

«Je ne crois pas qu’il était en notre pouvoir de changer les choses.»

(Houellebecq, 2022, p. 730)

«I don’t think it was in our power to change things» (Houellebecq, 2023, p. 616). This is the last sentence of the protagonist in anéantir. Seductive, if one considers how comfortable it can be to resign oneself and fall into the lap of nihilism. Provocative, if you ask yourself whether this nihilism is not the driving force that contributes most to the imbalances on our planet today.

From a universal point of view, the appeal of letting go is not necessarily out of place, if we think, for example, of the beliefs of some of our world religions, which are based on the longing for paradise or the return in eternities or cycles. With the latter, however, we should be aware that the consequence of letting go in the next round may be that there is no more room for us and our fellow species (unless we make it directly to Nirvana). To be reborn as a melting glacier or an overflowing ocean—who would want that?

An image from another of Houllebecq’s novels comes to mind. In «The Possibility of an Island» (in the original French, »La possibilité d’une île»), the transhuman being «Daniel 25» arrives at the end of a long journey at a sea that has almost disappeared in the anti-utopian world devastated by nuclear wars and environmental catastrophes. The sea, which he knows only from the texts of his predecessors, has changed, as «Daniel 25» is forced to realise:

«Ce paysage ne ressemblait guère, à vrai dire, à l’océan

tel que l’homme avait pu le connaître ; c’était un chapelet

de mares et d’étangs à l’eau presque immobile, séparés

par des bancs de sable ; tout était baigné d’une lumière

opaline, égale.»

(Houellebecq, 2005, p. 479)

«This landscape hardly resembled an ocean as people had known it; it was a chain of ponds and lakes of almost motionless water, separated by sandbanks: everything was bathed in a uniform, glittering light» (author’s translation).

While in the blog post Active Intuition (https://janeckert.ch/blog/active-intuition/) I reflect on my first trip to the French Atlantic coast in 2023, it was my second encounter with the ocean in the same year that brought the image from «The Possibility of an Island» to mind.

On an unseasonably hot September day, with temperatures of around thirty-six centigrade, there was little escape from the blazing sun on the seaward beaches of Cap Ferret. The «plage de la pointe» presented a scene that inevitably evoked the dystopian future of Houllebecq’s novel – and yet we were in the present.

Plage de la Pointe, Cap Ferret, France, 2023, Jan Eckert

The Second World War bunkers sinking into the sand were a reminder of the destructive past of the last century. At the same time, they seemed an all-too-current echo of the trench warfare raging once again in Europe. In the flickering backlight and through the spray whipped up by the sea breeze, a few silhouettes of other beachgoers could be made out. They did not seem human either, but rather like the transhuman being in Houllebecq’s novel who, at the end of a long journey, feels the need to lie down in the shallow water for good. At that moment, present and past, sea and sky, light and shadow, man and the silhouette of his own shadow merged. Had we already arrived in the nightmare of the «possibility of an island»?

History merging with a present without a future

French writer Sylvain Tesson recounts a similar fusion in his latest novel, «Blanc». For four years, Tesson crossed the European Alps from Menton to Trieste in four stages on touring skis, accompanied by mountain guide Daniel du Lac and a friend he met along the way.

«Dans la neige, l’eclat abolit la conscience»

(Tesson, 2022, p. 16)

«The splendour of the snow raises the consciousness» (author’s translation). With this thought, with this dream, Tesson begins the journey that, on the second day, brings nightmares from the past into consciousness:

«On skiait sur la piste blanche, à 2000 mètres. Casernes et fortins étaient semés comme des reposoirs. Nous passion la revue des ruines noires au milieu des fôrets féeriques. Autrefois, cette arête fut une ligne en feu. On s’y tua ardemment au milieu du XVIIIe siècle puis la Révolution. Bonaparte fit ses armes à l’Authion. On fortifia en 1930 on rempila en 1945. Dans ces sapinières pour reine des neiges, les batailles avaient servi à fixer les frontières d’une nation ou vivaient aujourd’hui des citoyens tranquilles qui n’aimaient pas les frontières.»

(Tesson, 2022, p. 23)

«We followed the white track at an altitude of 2000 metres. Barracks and small fortresses alternated like resting places. We looked at the black ruins in the middle of the fairytale forest. This ridge had once been a firing line. In the middle of the 18th century and during the Revolution, passionate killings had taken place here. Bonaparte earned his spurs here in Authion. It was fortified in 1930 and improved in 1945. In these pine forests for snow queens, the battles had served to define the borders of a nation whose innocent citizens do not like borders today». (author’s translation)

The snow, or perhaps the white sand of a beach or desert, seems to suspend consciousness. In addition to the scenes already described, more recent images from the press inevitably come to mind. Places used by some for recreation or entertainment seem to be used by others for their atrocities. Both are in their own way removed from our own consciousness, then and now. The juxtaposition of the two perspectives seems particularly perverse in a historical light.

Ski tour on the ridge of the Chasseral, Bernese Jura, January 2023, Jan Eckert

«I don’t think it was in our power to change things» Houellebecq could be quoted again. Weren’t many of the borders we live with today drawn before our time? Nightmare and dream of that time, too close and too far away, dissolve in the flickering backlight of the present.

A backlight that demands a counter-design. A design that puts things in the right light, as the saying goes, and through clarity creates silhouettes that can be read by future generations.

Boundaries

Before discussing the concept of design, hope and project-making in more detail, I would like to dwell for a moment on the concept of boundaries and how these, including the play of light and shade and their nuances, often become necessary in a globalised society that seeks to fulfil the promise of being «limitless».

The first encounter is with the work of the Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado. I will never forget going to a small cinema in Bologna years ago to see the film «The Salt of the Earth», co-directed by Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, the photographer’s son, and the German director Wim Wenders (Wenders, Ribeiro Salgado, 2014). Again, a scene of light and reflection: Salgado speaks to the audience, himself sitting in a cinema auditorium, his face illuminated by the projections of his photographs. They are his personal counter-design to the world and its horrors, which he has experienced not only through the lens of his camera, but also at first hand on his numerous reporting trips.

The consequences of these horrors are the illness of his immune system, the antipode of which has led Salgado to turn his attention to issues of regeneration of the planet and our environment.

These are the themes that he and his wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado, have been exploring in the Instituto Terra, which they themselves founded, and which they continue to explore through photography, exhibitions, and publications. The latest result of this exploration is the exhibition «Amazonia», which also came to Zurich in 2023.

Amazonia exhibition, Lélia Wanick Salgado and Sebastiao Salgado, Zurich, 2023 Image: Jan Eckert

My first impression on entering the room with the precisely lit prints was one of clarity. Although there are countless shades of grey between the black and white of Salgado’s photographs, they never seem random or mixed, but clearly separated as if by magic. For me, the result was an experience of immersion, made possible on the one hand by the large format of the prints, and on the other by the wondrous spaces in the scale from white to black into which one inevitably wants to dive.

The story that Leila and Sebastião tell in «Amazonia» is not only characterised by the unique light of the Amazon rainforest. It is also about boundaries and their transgression. There are boundaries between mountains, forests, streams, and the sky. Geographical boundaries that are subject to constant natural change. At the same time, there are boundaries that are constantly being crossed by humans; nature reserves, indigenous habitats, and the habitats of a multitude of other creatures that are under increasing pressure to adapt.

While Tesson’s travelogue tells of the man-made and historical boundaries that in some places are in conflict with the will of the people who live there today, Salgado’s «Amazonia» tells of the natural boundaries that must be respected or maintained to protect the inhabitants who live there. They are also increasingly in conflict with the interests of other groups of people who are putting pressure on the heart of life, the indigenous peoples’ habitat, and their livelihoods.

The planetary garden

The «Kepos» garden was the centre of the Epicurean school’s life, a place of interaction with nature, of living from the fruits of shared cultivation and of cultivating the mind. Similar to the examples of early paradise gardens, such as that of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae in modern Iran, they are early witnesses to a «hortus conclusus», the garden defined by its clear boundaries, both physical and philosophical. It is no coincidence that the image of the hortus conclusus was widely used in iconography and that the etymological origin of the word «garden» is characterised by its enclosure, the «walled enclosure».

It is precisely these boundaries that the landscape architect and gardener Gilles Clément seems to be breaking down with his concept of the «planetary garden». For Clément, it is not the idea or the human being that seems to be at the centre of the garden, but the planet. The walls of the hortus seem to be torn down, the boundaries of the garden and gardening dissolved. In «Toujours la Vie invente» (unfortunately I only have the English version «Life, Constantly Inventive» in «The Planetary Garden and other Writings» from 2015), Clément sums up his transgressive concept as follows:

«Instead of being limited to a small space that we control,

from now on the garden is placed within the limits of the biosphere.»

(Clément, 2008, p. 80)

Clément’s concept of the planetary garden becomes particularly tangible in his definition of the «Tiers Paysage», the «Third Landscape» (Clément, 2008, p. 83). Based on a binary division of the landscape into zones used for forestry and agriculture, Clément also defines «wild spaces in between» as the third landscape. He finds examples of this on roadsides or in wasteland that is difficult to access for agriculture. He summarises all this under the term «third landscape», which contributes to the diversity of the planet without human intervention. However, a closer look at Clément’s concept of diversity reveals a paradox to me:

«Endemism is Diversity through isolation, a diversity of creatures and of ideas. Geographic isolation and climatic barriers create as many environments where species appear. The more habitats (biotypes) there are, there more species there will be capable of living there and societies capable of developing. The longer the habitants remain isolated from one another, the longer diversity remains. It is expressed through the variety of individuals, behavior and beliefs.»

(Clément, 2008, p. 4)

An observation that can also be found in Salgado’s study of the Amazon; or in the aforementioned Silvain Tesson and his search for the eponymous wild cat described in «Pantère des neiges» (Tesson, 2019), which knows best how to merge with its limited habitat and isolate itself from the gaze of the seeker. However, the contrast between the planetary garden and the achievement of vital diversity through restriction and isolation led to many questions during my encounter with Gilles Clément’s concept. These in turn led to an ongoing exchange with my former professor and friend Prof. em. Eberhard Holder in Stuttgart, who has visited many historic gardens on his travels. Together we tried to resolve and understand the contradictions in Clément’s concept of the planetary garden. I would like to tell you more about the results of this exchange, but first I want to tell you about a third encounter with someone who is in his own way a master of diversity, its limits and its resolution.

The Planetary Gardener

My first encounter with Bruno Schloegel took place in 2022 and was completely impersonal in the truest sense of the word. At a natural wine fair in Gothenburg, Sweden, I had the pleasure of tasting his Alsatian wines with a local merchant, Otto Karlsson from Rekovin—wines that spoke for themselves and for Bruno himself. So much so that after a whole day of tasting about five dozen wines, I would only remember his. In the autumn of 2023, after a long wait, I had the opportunity to visit Bruno in Alsace and get to know him, his work, his terroir and his wines.

To put the whole experience of that afternoon in Wolxheim into words would probably require another text. Starting with a tasting of Bruno’s products, or his «co-productions with the terroir», made from different grapes, sites and vintages, we were able to get a glimpse of the underlying boundaries, which I would like to write more about here.

Co-productions of the Terroir and Lissner Vins d’Alsace, Wolxheim, 2023, Jan Eckert

The wine connoisseurs among the readers will probably think: «But that’s obvious. Wine tastes different depending on the grape variety, origin or vintage». This is probably true, but with Bruno’s wines it is the nuances that come from a unique depth that make the difference. Perhaps a little like the countless shades of grey between the black and white of Salgado’s photographs. Suddenly, it is no longer the red or white, early-pressed, golden or ruby wine that has undergone another process of maceration, but another nuance. In the words of Verlaine from his „Art Poetique“ (Verlaine 1882), one could say:

„Car nous voulons la Nuance encor,

Pas la couleur, rien que la nuance!“

(Verlaine, 1882)

„Because we still want the nuance, not the colour, just the nuance!“ (author’s translation). And what a richness of nuances unfolds before our eyes as we enter the autumn vineyards around Wolxheim with Bruno. Innumerable shades of colour, innumerable plots of land lined up, seeming to merge and yet precisely separated in the Alemannic way (one part of Alsatian culture). «You can recognise my parcels by their particularly ripe colour», explains Bruno, «partly because I don’t defoliate the vines and allow them to ripen to perfection». This, in turn, has to do with the biodiversity that Bruno tries to promote on his plots by allowing other plants to take up space between the vines—as we were later to learn.

That’s when I began to understand how the paradox of Clément’s planetary garden began to unfold in front of me. A multitude of winegrowers, working a multitude of plots separately from each other, were creating diversity, both in the way they cultivated the vines and treated the terroir, and in the resulting wines and flavours. The differences in biodiversity could not be greater, of course, which is why I am particularly impressed by Bruno’s clear attitude and continuous work.

Bruno’s vineyards in Wolxheim, Alsace, 2023, Jan Eckert

When we took a closer look at one of Bruno’s plots, the interplay between boundary and delimitation became even clearer. Compared to the neighbouring plots with their neatly separated vines, Bruno’s vines grow in a community of soil, plants and the countless animals that live there—a wild growth, one might think. «Vin sauvage-vin vivant» is Bruno’s opinion.

«Dans le vignoble de Bruno, li n’y a pas de murs

-il ya une coexistence entre les êtres vivants.»

During a visit to Wolxheim, 2023

«In Bruno’s vineyard, there are no walls, only coexistence between living beings». This is how I captioned one of the photos I took during my visit to Bruno’s vineyard, which Bruno kindly published on his Lissner Vins d’Alsace website (lissner.fr). It’s not just the variety of creatures living together on Bruno’s plots, but also the boundaries that Bruno has broken with his vision of biodynamic viticulture, as well as the boundaries that are still part of the complex system. For example, the hedges that separate Bruno’s plot from his neighbours and their pesticides, or that keep out the cold wind and protect the vines.

I do not have the expertise to understand all of this in detail, so I can only encourage you to read Bruno’s many texts (many of which are available on his website); or even better: come and see for yourself how Bruno’s dream of biodynamic viticulture, based on coexistence and cooperation with the planet, has taken shape. A project, a dream that has required almost a decade and a half of Bruno’s work to regenerate the land and the vineyards.

«I define the garden as only territory where

man and nature meet, in which dreaming is allowed.

It is in this space that man can be in a utopia

that is the happiness of his dreams.»

Clément, 2008, p. 82f

Encounter between dream, man and nature

«I define the garden as the only territory where man and nature meet and where dreaming is allowed. In this space, man can be in a utopia that embodies the happiness of his dreams». This is what Gilles Clément writes in one of his texts (Clément, 2008, p. 82f). It is here that the concept of dreaming, which I had anticipated in the introduction to this text, comes to the fore.

As already mentioned, it took a longer exchange to understand Clément’s concept better. An exchange that took place through the joint sending of analogue and digital sketchbook entries and dealt with questions relating to planetary gardening. For example, my friend Eberhard and I asked ourselves: Do we need the boundaries I have written so much about in this text? What is planetary or global? Do we need a kind of community, a collective or a club, oriented towards a common consciousness, in order to cultivate the planetary garden? Do we even need rules, a kind of charter? The areas of tension that have emerged in our dialogue on the Hortus are certainly interesting. Here are a few examples:

order vs. chaos

planning vs. serendipity

consumption vs. participation

self-realisation vs. self-knowledge

ego vs. collective

pride vs. modesty

show/experience vs. embodiment*

*Embodiment is used here as understood by the neuroscientist Francisco J. Varela (Varela et al., 2016).

One element we began to write about again and again was that of «serendipity», the acceptance of the unexpected, the unplanned, the chaotic, the determined. An alternative concept to Houellebecq’s renunciation of the possibility of change, because with serendipity change lies precisely in being open, in actively accepting to change. I tried to describe this in the previous blog entry as «Active Intuition», as a counter-proposal to the term «Active Inference» coined by neuroscientist Karl Johan Friston (Parr, Pezzulo & Friston, 2022), which describes the constant anticipation and weighing of possible futures.

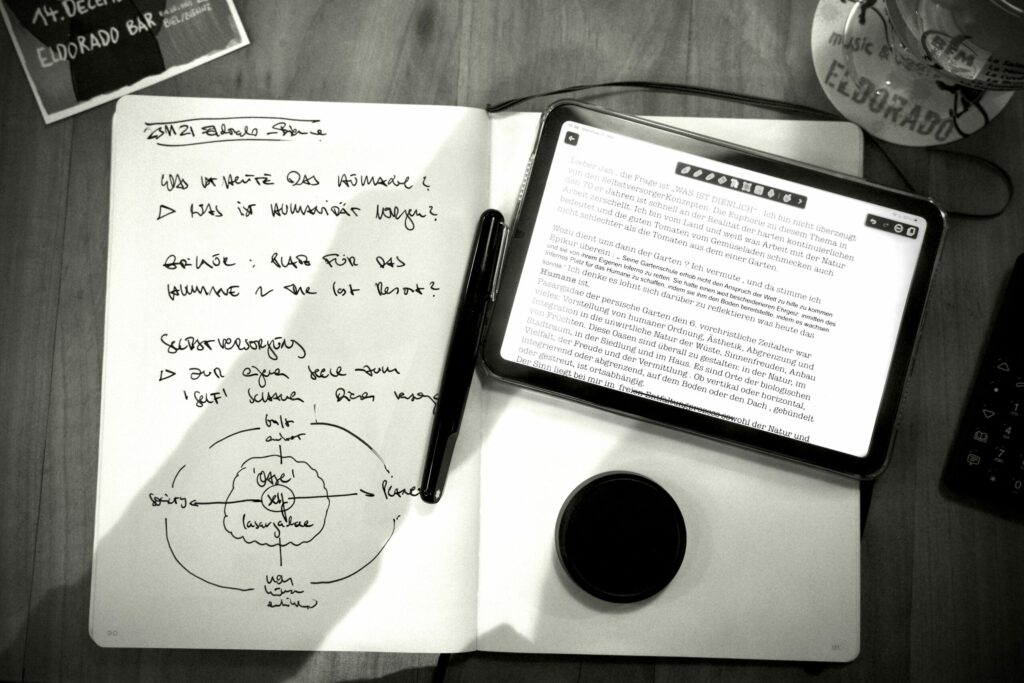

Sketchbook entries, analogue and digital, 2023, Eberhard Holder and Jan Eckert

This creates a tension between planning the environment and accepting what may emerge from cooperation with other forces. «vin sauvage—vin vivant» is perhaps how Bruno Schloegel would describe this tension resulting from his co-creation with the terroir. After much reflection and further dialogue, Eberhard and I found another quote from Gilles Clément that aptly sums up this tension in the context of the planetary garden:

«At the heart of the garden, the uncontrolled forces of life and its inventions,

the dream of man und his utopias, both defining from one day to the next

the unpredictable trajectory of evolution.»

(Clément, 2008, p.33)

Both the human dream and the autonomy of nature have their place in this definition. It is in this field of tension that space is created for the above-mentioned counter-designs, from which our world today can only benefit.

Design and hope

From a neuroscientific, cultural or spiritual perspective, the concept of dreaming can take on different meanings. It can be assumed that Gilles Clément’s dream does not exclude any of these facets. In the following, I would like to pick out one of these facets and take a closer look at it. The dream as a projection, as a design of the future, or as Otto Scharmer describes it in his Theory-U established at MIT: «Learning from Emerging Futures» (Scharmer, 2018).

In his essay «Demokratie und Gestaltung» (Bonsiepe, 2009, p. 15 ff.), the German designer and design theorist Gui Bonsiepe, who lives in Latin America, reflects on the perspective of the recognisability of certain sciences and contrasts it with the perspective of the designability of design sciences – two perspectives that, as he notes, would ideally complement each other. Overall, Bonsiepe highlights the ontological perspective of design in the compendium «Entwurfskultur und Gesellschaft» (Bonsiepe, 2009). A perspective also explored by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley in their book «are we human? notes on an archology of design» (Colomina & Wiley, 2021), which analyses human history and design.

«We live in a time when everything is designed,

from our carefully crafted individual looks and

online identities to the surrounding galaxies

of personal devices, new materials, interfaces,

networks, systems, infrastructure, data, chemicals,

organisms, and genetic codes»

(Colomina & Wiley, 2021, p.9)

«All this is design – or more precisely: all this is project-making», Bonsiepe would reply (Bonsiepe, 2009, p. 210, author’s translation). Just as he does in his essay «Entwurf und Entwurfsforschung—Differenz und Affinität» when commenting on Hal Foster’s observation that design encompasses everything «from jeans to genes» (Foster, 2002, p. 17). From these reflections it is clear that design is in nature, and if one adds Clément’s perspective, it is a perspective that is not only in human nature, but seems to be universal.

There is another text by Gui Bonsiepe that takes up this perspective. More precisely, it is one of his translations of texts by Tomás Maldonado, the last rector of the Ulm School of Design and probably one of the most underrated design theorists in the German-speaking world. It is the German translation of Maldonado’s «Speranza Progettuale», which Bonsiepe published in 1972, two years after the original Italian version, under the title «Umwelt und Revolte: zur Dialektik des Entwerfens im Spätkapitalismus».

Before I go into this text in more detail, however, it is important to understand the nuances of the term «designing» or «entwerfen» in German, as used by Gui Bonsiepe. It may be helpful to look at its Italian equivalent, «progettare». Literally translated, it means «gettare avanti» or: to project oneself, a situation or a state into the future in order to help shape or change it. And isn’t there an interesting parallel here with the dream element in Gilles Clément’s Planetary Garden?

But back to Maldonado’s «Speranza Progettuale». It is a text that unfolds its enormous potential more and more as our socio-economic systems reach their so-called tipping points, and as the extent of these tipping points becomes more concrete, the consequences for our shrinking habitat become more unpredictable. While this is primarily discussed in the seventh chapter of the German edition of Speranza Progettuale, translated by Bonsiepe, the core of the multi-layered text is the act of designing (progettare) as an optimistic alternative to social, political and ecological nihilism. And if we agree that nihilism is one of the driving forces that can lead to our extinction, as I have already written in this text, then the term «hope» (Italian: speranza) takes on its full meaning in the act of designing, as proposed by Maldonado as a counter-model.

It is a text that could not be more relevant today. And while a new edition of the original Italian version of «Speranza Progettuale», curated by Raimonda Riccini and Medardo Chiapponi, was published by Feltrinelli in 2022, the German translation is currently out of print and German-speaking readers have been waiting a long time for its return.

If we now place the concept of design and hope once again in the context of the planetary garden, «dream» or «dreaming» takes on a new meaning, and perhaps it will also become clearer what I meant in the previous sections by «counter-design» to the destructive, nihilistic or contourless designs of people in their relationship to themselves, to their fellow creatures and to our common habitat that are currently present in many places. But what might such a counter-design look like?

«(…) a mental territory for optimism; a garden.»

(Clément, 2008, p.112)

Hortopia

«Hortopia»—that’s what we called this design in dialogue with Eberhard for the moment. The garden in the broadest sense, a mental and physical place for dreams and designs to guide the largely unpredictable paths of evolution towards an optimistic future.

This is how Gilles Clément describes it: «(…) a mental territory for optimism; a garden.» (Clément, 2008, p.112). And while his quote may have the nuance of a place of refuge, «Hortopia» is meant to be a place of departure. In this text, I have written about breaking down borders, about setting out into uncertain territories or futures, reflecting on the works of Salgado, Tesson or Houellebecq. For me, the most concrete way to shape the future is to imagine Bruno Schloegel’s dream and his implementation of biodynamic viticulture in Wolxheim. It is in his work that not only Hortopia but also Maldonado’s optimistic call to action becomes concrete for me.

«This time it really is the last time», assures Hans Ulrich Obrist before formulating the final question of his 2006 interview with Tomás Maldonado. Originally commissioned by Stefano Boeri, then editor-in-chief of Domus, Maldonado and Obrist revisited the text in 2009, after Boeri’s departure from Domus, and the interview was published by Feltrinelli in 2010 under

the title «Tomás Maldonado-Arte e artefatti-Interivsta di Hans Ulrich Obrist». Hans Ulrich Obrist’s final question in the interview, which took place forty years after the first edition of Maldonado’s Speranza Progettuale and eighteen years before his death, is to what extent Maldonado would still subscribe to his thesis of hope arising from the designability of our world.

Maldonado denies this, explaining that both the extension of the concept of design to a multitude of meanings and a «principle of hope», as formulated by the German philosopher Ernst Bloch, are not sufficient to face the increasingly complex world, which requires a more proactive attitude. As an alternative to the «principle of hope», Maldonado proposes transformative action through positivity, which on the one hand requires constant «observation based on a critical spirit» (Maldonado, Obrist, 2010, author’s translation). On the other hand, Maldonado quotes the Italian singer-songwriter Lorenzo Cherubini, also known as «Jovanotti», for this purpose, shifting the realm of shapeability of our world to a level that may seem banal at first glance—positivity and the act of shaping rooted in the fact of being alive:

«Io penso positivo perché son’ vivo – perché son’ vivo»

Jovanotti (1993)

This really is the last paragraph—and I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has read this far. With these thanks comes the (New Year’s) wish that, in this time of glaring backlit shadows of an uncertain future, we can not only nourish our own vitality through lived optimism, but also discover appropriate territories for dreaming in the sense of «Hortopia», and perhaps even dream up one or two transformative counter-designs.

Sunrays on the first snow cover of the year, Bernese Jura, 2024, Jan Eckert

Bibliography

Bonsiepe, G. 2009. Entwurfskultur und Gesellschaft—Gestaltung zwischen Zentrum und Peripherie. Birkhäuser. Basel.

Clément, G. 2015. The Planetary Garden and other Writings. University of Pennsylvania Press. Philadelphia.

Colomina, B., Wiley, M. 2021. Are we human? Notes on an archeology of design. Lars Müller Publishers. Zürich

Foster, H., 2002. Design and Crime. Verso. London

Houellebecq, M. 2005. La possibilité d’une île. Librairie Arthème Fayard.

Houellebecq, M. 2022. anéantir. Flammarion.

Jovanotti. 1993. Penso Positivo. 5:05min. Auf dem Album Lorenzo. Mercury.

Maldonado, T. 1970. La speranza progettuale. Ambiente e società. Giulio Einaudi. Torino.

Maldonado, T. 1972. Umwelt und Revolte: zur Dialektik des Entwerfens im Spätkapitalismus. Übertragung aus dem Italienischen von Guy Bonsiepe. Rowohlt. Reinbek bei Hamburg.

Maldonado, T. Obrist, H.U. 2010. Tomás Maldonado—Arte e artefatti—Interivsta di Hans Ulrich Obrist. Feltrinelli. Milano

Parr, T. Pezzulo, G. Friston, K.J. 2022. Active Inference—The Free Energy Principle in Mind, Brain and Behaviour. MIT Press. Cambridge. London.

Scharmer, C. O. 2018. The Essentials of Theory U—Core Principles and Applications. Barrett-Koehler. Oakland.

Tesson, S. 2019. La panthère des neiges. Editions Gallimard

Tesson, S. 2022. Blanc. Editions Gallimard

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., Rosch, E. 2016. The Embodied Mind—Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Revised Edition of the original 1991 text. MIT Press. Cambridge. London.

Verlaine, P. 1882. Art Poétique. In Paris Moderne. Revue littéraire et artistique. Vol. 2, 1882/83, November 10, 1882, pp. 144-145

Wenders, W. Ribeiro Salgado, J. 2014. The Salt of the Earth. Wenders, Rosier. 110min