image above: Kohei Saito’s guest lecture at ETH Zürich, 6th of November 2024, Jan Eckert

It was a privilege and a pleasure to meet Japanese philosopher Kohei Saito and attend his guest lecture on “Climate Change, Degrowth and Communism”. Many thanks to the IEA Institute for Design and Architecture at ETH Zurich for inviting him. His books “Marx in the Anthropocene” (Saito, 2022), and “Slow Down – The Degrowth Manifesto” (Saito, 2024a) have been very inspiring to me and a great inspiration for my latest project hortopia.org. But how much better is it to meet such a great thinker in person and exchange ideas!

At Switzerland’s most prominent school of architecture, Saito began by critically questioning whether this was the most appropriate place to explore the concepts of degrowth, given the field’s deep entanglement with capitalist development dynamics. He provided a poignant example from his home city of Tokyo, where current urban projects often seek to exploit and replace natural and historical sites with commercial sports facilities, offices and high-rise shopping complexes – all while attempting to greenwash these endeavours by incorporating symbolic urban gardens or recreational spaces.

This vivid case study, as well as our architectural world in general, served to illustrate the persistent tensions and conflicts that are constantly built into the fabric of the built environment – what I have previously described in my systems thinking lectures as an ‘area of friction’ where these contradictions manifest themselves.

To summarise all of Saito’s writings and the Zurich lecture would certainly be beyond the scope of this text, but here are some of the concepts that resonated most with me from Saito’s writings and the Zurich lecture:

Metabolism

Based on his extensive study of Marx’s late, unpublished notebooks, Saito explores Marx’s nuanced understanding of “metabolism” or “Stoffwechsel” – the dialectical processes and relationships between human and non-human entities. And, as we shall see, Marx was well aware of the tipping points of these relationships and went on to explore ecology and pre-capitalist approaches to finding a balance in the constant metabolism inherent in the human-non-human relationship. I highly recommend reading Saito’s “Marx in the Anthropocene” (Saito, 2022) for those who wish to delve deeper into this topic.

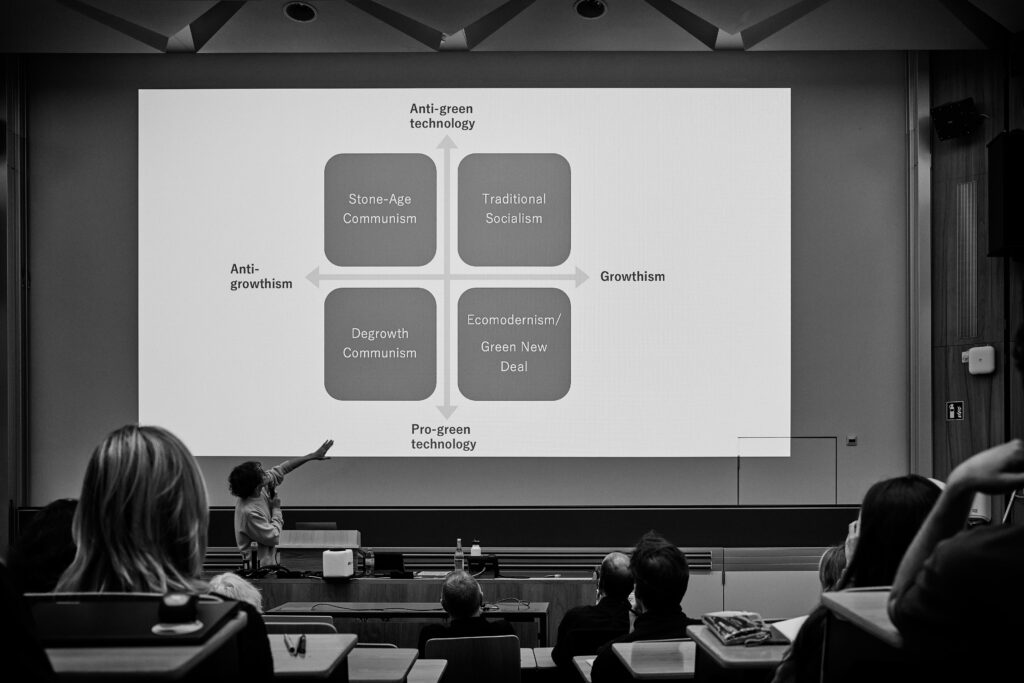

Ecomodernism

It is clear that many of today’s global injustices and inequalities are the result of a neoliberal, capitalist and globalised world. But Saito argues that even approaches such as traditional socialism, social democracy or the globally promoted “Green Deal” may ultimately fail to adequately address growing global inequalities and the human-ecosystem imbalance. This is because these frameworks remain rooted in the underlying logic of growth, exploitation of scarce resources and the perpetuation of scarcity.

Kohei Saito during his lecture at ETH Zürich, 2024, Jan Eckert

Degrowth Communism

In response, Saito proposes his vision of “Degrowth Communism” – a paradigm centred on the notion of common goods, values and a more constructive, emancipatory relationship with technology and scientific progress. During the question and answer session, some participants questioned whether the historical baggage of ‘communism’ might hinder the widespread acceptance of such an approach – a criticism with which, as a child of former Eastern Bloc emigrants, I am inclined to agree.

How can an inclusive degrowth dialogue be facilitated?

A key question I asked during the Q&A session was how to facilitate a truly inclusive, participatory dialogue on degrowth, given that the populations that have benefited most from the current capitalist order are unlikely to have an inherent interest in initiating or enabling such a transition. Saito explained that this dialogue is most likely to emerge from the margins, the exploited peripheries of the system, driven by the escalating crises of climate change, resource scarcity and geopolitical conflict. Perhaps for this reason, Saito explains that his next project, which he has begun at the New Institute in Hamburg, is to use the war economy as a baseline to expand the concept of degrowth into possible futures – certainly futures that are already a reality in some parts of our world, but that we do not want to replicate globally.

Towards public luxury and private sufficiency

Perhaps the most directly applicable aspect of Saito’s lecture for me was his concluding thoughts on the possibility of achieving a “post-scarcity economy based on public luxury and private sufficiency” (Saito, 2024b). And basically this transformation is based on shifting our values and needs from consumerism to some basic qualities of life. This can still include paying your rent, your gas bill for heating in the cold season, but it can also mean shifting from a wealth-oriented to a less work-oriented and more socially qualitative worldview, resulting in fewer working hours, more leisure and social time, more time for caring, mutual aid and spirituality.

I have to say that I was very inspired by this last part, as it has a lot to do with the themes of my latest project, hortopia.org, and how it extends the traditional notion of the garden into an eco-social framework that includes concepts of sufficiency, care and spirituality. “Urbanism of Care”, “Qualities of Dreaming” and “Re-Negotiating Space” are some of the projects and examples that link hortopia to Saito’s concept of degrowth, public luxury, private sufficiency and care.

Designeability of Care as one way towards Degrowth?

In closing, I would like to return to the concept of “Speranza Progettuale” (Maldonado, 1970, newly published in 2022), a seminal work by the late Tomás Maldonado, which expands the ontological dimension of design (artefacts, sociofacts or mentifacts) and elevates it to a “designability of hope”, referring to Ernst Bloch’s “principle of hope” (Bloch, 1959) and the optimist-creative potential of design.

While today’s polycrisis is characterised by complexity and volatility that often lead to resignation and nihilism in the light of designability, I believe that there are still ways to approach this overwhelming complexity with humility, optimism and creativity. Which is why I would like to refer to systems thinker Donella Meadows and her thoughts on “dancing with a system”, which includes the notion of “expanding the boundaries of care” (Meadows, 2004, 2008).

Similar to the “designeability of hope” coined by Maldonado, I believe there is a “designeability of care”. And by linking to hortopia as a concept of the extended planetary garden, it is indeed a territory of care that can co-evolve within all the frictions between human and non-human populations. A very interesting territory to explore with the notion of degrowth, I think.

References

Bloch, E. (1980). Das Prinzip Hoffnung. Bd. 3: 5. Teil; S. 1089 – 1655] / [Bloch, Ernst (7. Aufl, Vol. 3). Suhrkamp.

Maldonado, Tomás. (2022). La speranza progettuale: Ambiente e società (M. Chiapponi & R. Riccini, Eds.). Feltrinelli.

Meadows, D. H. (2004). Dancing with Systems. Timeline Magazine, #74(April 2004). https://www.globalcommunity.org/timeline/74/index.shtml#1

Meadows, D. H., & Wright, D. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Pub.

Saitō, K. (2022). Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the idea of degrowth communism. Cambridge University Press.

Saitō, K. (2024a). Slow down: The declaration manifesto (B. Bergstrom, Trans.; First edition). Astra House.

Saitō, K. (2024b, November 6). Climate Change, Degrowth and Communism [Guest Lecture].